l'Abbé Hadol

Martyr of Gemmelaincourt

The new parish priest in the village

In 1758, the church of Saint-Maur in Gemmelaincourt (then Gemmenaincourt) received a new parish priest by the name of Maximilien-François-Gabriel Hadol. Although Hadol had been ill since childhood, he had a strong desire to get to know his parishioners, gain their trust, teach them and encourage them to appreciate and practise Christian virtues. He also took on the secular tasks associated with the parish office with great commitment. After Father Hadol had overcome several challenges in the parish, including disagreements with the Lord of Gemmelaincourt, a d'Hennezel, he could hope for a peaceful and happy retirement.

The oath to the civil constitution

When the French Revolution broke out in 1789 with the storming of the Bastille, Father Hadol was already 59 years old. At the beginning of 1791, Father Hadol took the oath of allegiance to the "Civil Constitution of the Clergy" (French: "Constitution civile du clergé"), as prescribed by the law of 1790. The law aimed to reform the Catholic Church in France and bring it under state control by giving the government authority over all church matters, including the appointment of bishops and priests and the administration of church property. While some clergy took the oath, others refused, leading to conflict between supporters of the revolution and loyal Catholics.

Priest Hadol remained true to his oath for eighteen months until he publicly recanted it in front of all his parishioners in the Saint-Maur church. The people were so angry that they insulted, pushed and beat him and he was forced to flee the parish.

During the French Revolution, the laws began to become stricter. The law of 26 August 1792, for example, required clergymen to either take the oath or leave the kingdom within a fortnight. In addition, those clergymen who were not under oath had to apply for a passport. Those who applied for and received a passport but remained in the kingdom or returned after leaving it were subject to long prison sentences.

"I swear to carefully oversee the faithful of the diocese or parish entrusted to me, to be faithful to the nation, the law and the King, and to uphold with all my strength the Constitution enacted by the National Assembly and approved by the King."

- Compulsory oath for bishops and priests: Constitution civile du clergé of 12 July 1790

The denunciation of Priest Hadol

On 9 September 1792, Hadol had a passport issued for Deux-Ponts in the Palatinate. In the passport, the clergyman was described as follows: Sixty-two, height 4 feet 10 inches (about 1.57 metres), wig, chestnut eyebrows, grey eyes, water nose, ordinary mouth, oval face. It is not clear whether he left the kingdom with his passport or remained in the country. However, this was ultimately irrelevant because, as already mentioned, both staying in the country and returning to the kingdom were punished with the same severe penalty. We know for certain that the priest Hadol travelled from village to village before his arrest, hiding under various disguises and selling yarn, needles, pins, knives and homemade scissor chains. In Nancy, he was occasionally given shelter by a young nun called Marie-Elisabeth Antoine. As he was once again staying with the nun and strolling through the streets of Nancy, a young girl from Gemmelaincourt recognised him under his disguise and greeted the old priest with joy and affection with the words: "Good afternoon, Father." Sixteen-year-old knitter Anne Ethelin must have overheard this and incited passers-by against the poor priest and reported him to the district authorities. On 27 May 1794, the priest Hadol was arrested and put on trial.

Conviction and punishment

The law of 29-30 Vendémimaire II (20-21 October 1793) further tightened the already strict legislation. Among other provisions, the law of the Vendémiaire declared all exiled clergymen who returned or had returned to the territory of the Republic, as well as those who had recanted their oath and evaded exile by hiding, to be condemned to death.

The trial against Hadol began on 2 Messidor II (20 June 1794) at nine o'clock in the morning. The president, the three judges, the public prosecutor and the court clerk took their seats while the defendant sat opposite them. The evidence lay on the table: priestly ornaments and undoubtedly counter-revolutionary printed matter. The court president began questioning the accused. The nun Antoine and various other witnesses were then questioned. Towards the end, the public prosecutor rose to support the charges and demand the application of the law. The judgement was merciless, as the law demanded. It was considered proven that Hadol had remained in the territory of the Republic and had practised Catholic worship there as a fanatical and rebellious priest. There was only one punishment for this. The former priest of Gemmelaincourt went to the scaffold in Nancy's Place de la Liberté the next day, 21 June 1794. He died, it is said, with great courage. His possessions, a silver watch and a copper key, were confiscated and auctioned off on 18 Fructidor II (4 September 1794). Jean-Baptiste Leclerc won the auction with his bid of 108 pounds. The informer Anne Ethelin received a reward of 100 pounds for her denunciation.

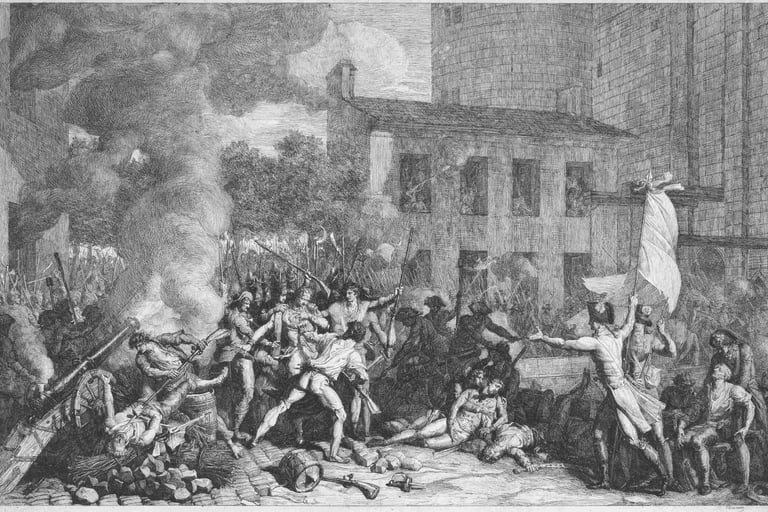

Storming of the Bastille (14 July 1789)

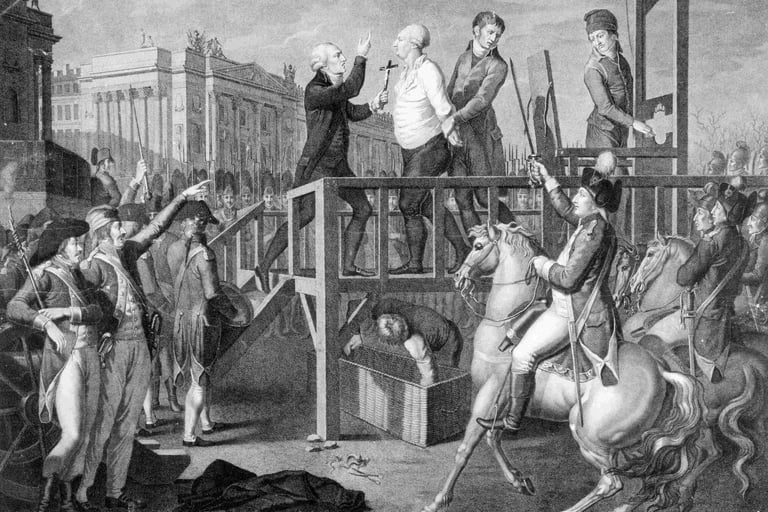

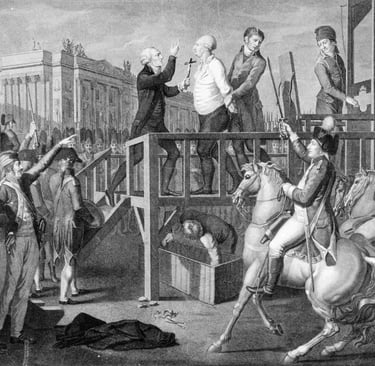

The last moment of the monarch Louis XVI (21 January 1793)

The overthrow of Maximilien Robespierre in the National Convention (27 July 1794)

Coup d'état on 18 Brumaire VIII (9 November 1799)

Images of the French Revolution

Saint Maur (Saint Maurus) today

SOURCES

Albert Troux, "La Révolution en Lorraine", Nancy 1931

books.google.ch

de.wikipedia.org

Eugène Mangenot, "Ecclésiastiques de la Meurthe, martyrs et confesseurs de la foi pendant la Révolution française", Nancy 1895

CONTACT

Le Jadin des Lys

8 rue de la Fontaine

88170 Gemmelaincourt

info@gemmelaincourt.com

Legal Notice & Privacy Policy